Othello’s occupation will be gone; but he will remain Othello. The young airman up in the sky is driven not only by the voices of loudspeakers; he is driven by voices in himself—ancient instincts, instincts fostered and cherished by education and tradition. Is he to be blamed for those instincts? (Woolf, The Death of the Moth)

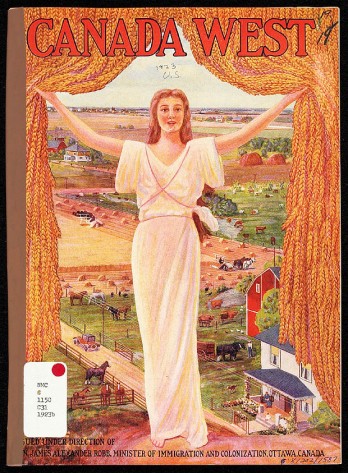

Othello, (1623 First Folio)

Traces of Othello emerge in Virginia Woolf’s first chapter of Orlando (1928) as an artistic and literary strategy to make present the influence of education, tradition, and ancient voices enacted in the violence against women and the eradication of their voices. Woolf does not merely resurrect the ‘dead,’ early modern characters of Othello and Desdemona, with whom the living could experience a temporal connection; she disrupts early twentieth century cultural and national literary hegemony to effect historical and literary change. Woolf’s intertextual methodology is not containable; it is not static nor is it isolated in a desire for meaning. For Woolf, her writing provides the agency through which to explore the variant social, political, and cultural ideas available for interpretation; Woolf does not give answers; she leaves a space for critical inquiry into the violence recorded through loudspeakers and literary canons.

I continue to return to Erica L. Johnson’s essay, “Giving up the Ghost: National and Literary Haunting in Orlando” and her reference to Derrida’s hauntology theory. Johnson suggests “for Woolf … to be haunted is to hear silence and to perceive that which is invisible” (110). Woolf’s intertextual use of Shakespeare brings forward the absent/presence of women, and one represented “silence” is particularly deafening: Desdemona, the suffocated woman in her bed (Woolf 43).

But why Othello? In the first chapter of Orlando Woolf directs her reader to the act of decoding, a semiotic to-do list for “those who like symbols, and have a turn for the deciphering of them” (5). The deployment of an Othellian allusion is not simply Woolf’s literary cunning to cite another author in order to conjure meaning. Othello’s specter haunts Woolf’s text because of the ancient voices that reside within Woolf, and thereby, manifest as symbols to register the reader’s responsibility to decipher. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in her essay, “Notes Toward a Tribute to Jacques Derrida,” addresses Derrida’s theory that “the public part of mourning is a not unimportant step in the releasing of the ghost, in us. We cannot know the gift, least of all a giftcoming from a named ghost. We know the gift, if there is any, as responsibility, accountability” (102). Woolf’s gift is through her use of codes. In her compilation of essays in The Death of the Moth, for instance, Woolf questions the voices over loudspeakers and those ancient instincts fostered and cherished by education and tradition that cornerstone the pedagogical building of patriarchal hierarchies and their associative violence specifically in literary, historical, and biographical texts (par. 7). Woolf expects the reader “to know” Orlando’s Shakespearean associations which were garnered through traditional education. Woolf’s own education, fostered by the bookshelves in her father’s library, brings forward her personal catalogue of voices that manifest in the figure of Orlando, in an attic haunted by his violent association, and in his patriarchal and colonial African past (Orlando 11).

Woolf’s biography of a woman writer traced through four centuries of English literary history is based on the life of Woolf’s lover, Vita Sackville-West.

The play Othello is a Shakespearean tragedy written in 1603 during the reign of King James. Crossing a spectrum comprising racism, misogyny, betrayal and power the lead figure Othello is cast as “a Moor.”[1] His character’s lineage, in the play text, is not designated, and thereby, distinguishing Othello as “a Moor” could mean a Muslim, Arabic from sub-Saharan African descent. Woolf’s reference to “a Moor” however is distinct and locates him in the violent history of Orlando’s colonizing forefathers in Africa (11). Benedict Anderson argues that in Woolf’s Orlando, in “the modern world everyone can, should, will ‘have’ a nationality, as he or she ‘has ‘a gender’ (Hovey 1). The statement infers not only a merging of gender and nation but a construction that is tantamount in the first page of Woolf’s novel. By intersecting nationality, gender and race, Woolf documents a retrospective subtext detailing the violence made present in Orlando’s attic, a slicing of a Moor’s head. Woolf’s simultaneous posturing and declaration that Orlando is “HE – FOR THERE could be no doubt of his sex” (1), genders the colonizing brutality and signals the anxiety of identity while identifying how nations and identities are chronicled and, ironically, fall into the cultural violence of amnesia. Why do the lips on the head, as it falls, reveal a smile? The violence against the figure of Othello is situated but not heard. The history from the Moor’s voice is not recorded and a specific irony captured in the lips of the nameless history haunts Orlando’s attic.

Woolf’s narrative redistributes a textual and visual mourning, a memorial that lets go of literary ghosts and, through varying historical manifestations, are essentially “in us.” The attic, therefore, is a metaphor, a space of unforgetting the violence of colonization not only of territory but also of individual bodies.

“It was the colour of an old football, and more or less the shape of one, save for the sunken cheeks and a strand or two of coarse, dry hair, like the hair on a coconaut. (Woolf, Orlando 12)

Woolf’s metonymic link to sport in “football” and to “cocoanut” (sic) demonstrates the practice of exotification and signals a performance space where ancient voices manifest and inform the actions of Orlando:

Orlando’s father, and perhaps his grandfather, had struck it from the shoulders of a vast Pagan who had started up under the moon in the barbarian fields of Africa; and now it swung, gently, perpetually, in the breeze which never ceased blowing through the attic rooms of the gigantic house of the lord who had slain him. (1)

Here, the slain “Moor” is abject and Other and carries the codes of imperial violence.[2] Johnson in her essay suggests that because Woolf works out her “conflicted stance on national identity through haunting, cultural theories, and cultural applications of Marxist and psychoanalytic theory are of particular use. For Woolf and these thinkers, to be haunted is to hear silence and to perceive that which is invisible” (1). The encoding of “smiling lips on the head of the Moor” signifies the loss of agency to Orlando and presents a powerful irony because he will never know the history behind the smile of the Moor, and as postured, the figure of the Moor has the last laugh. Simultaneously, the symbol establishes the unrecorded stories, a major theme in Woolf’s text. In addition, Woolf also raises the figure of the Moor with intertextual associations in Ǽthelbert: A Tragedy in Five Acts (13). The play could reference the historical writing of Aethelbert, King of East Anglia, who, during his reign was a subject of plots that led to his beheading (DiBattista 257). The allusion physically conflates imperial, territorial, linguistic histories in the slicing of the head, a specific violence found in Woolf’s text when she describes that the “soldiers planned the conquest of the Moor” (26). Maria DiBattista, who wrote the Introduction and Annotations to the Harcourt edition of Orlando, further explains Woolf’s symbolism of “fields of asphodel” (11): “Orlando’s ‘fathers’ roamed, it seems, in actual fields of asphodel, a lilylike plant that the ancients believed to be the favorite food of the dead and so planted them near graves. The irony is deployed in the realization that the Greek myth made no connection to virtue or evil in the symbol, yet early English poetry used the symbol to represent chivalry (257). Woolf also draws upon the allusion of Robert Green’s characterization of Orlando Furoso, the figure DiBattista suggests Woolf’s character’s name is based on (256). Consider the following passage from Green’s edition:

The savage Moors and Anthropophagi,

Whose lands I pass’d, might well have kept me back;

…

But so the fame of fair Angelica

Stamp’d in my thoughts the figure of her love,

As neither country, king, or seas, or cannibals,

Could by despairing keep Orlando back.

I list not boast in acts of chivalry (par. 6)

From the opening of Orlando, Woolf uses the past to spin multiple translations and interpretations. But how does one detect the invisible and the silence when the text is not supplemented with annotations? How does one identify the undetectable, the lost stories, the women cut down as they ran through the African fields, the words Desdemona said the moment before she was strangled? How does one know for certain that even though the Moor is constructed as male, as Orlando is, that the gender may not represent a woman, a gender-switch made concrete in a seventeenth century Desdemona played by a young boy. The haunting, then, becomes like the Spur on the narrative forest floor, intertextual and organic traces of voice or what Derrida calls, trace. For Woolf, she brings forward the trace of Othello.

Othello (adaptation by Frantic Assembly), 2008

Spivak, in her article, asks the question: What, then, is a trace?

It is or is not, or, more important, is in the possibility of always not being, the material suggestion that something else was there before, something other than it, of course. Unlike a sign, which carries a systemic assurance of meaning, a trace carries no guarantees. Animal spoor on the forest floor (in German, trace is Spur) may mean the animal was there, that it’s a decoy, that I am mistaken or hallucinating, and so on. When I am around, you know I had a mother, but that is all … I am my mother’s trace. The Father’s name is written within the patronymic sign system. (104)

Derrida’s allusion to father and mother is iterated in Woolf’s opening passage with Orlando’s inner call to go to the field of Africa:

He would steal away from his mother … and go to his attic room and there lunge and plunge and slice. (1)

The trace in this passage is Orlando’s mother as unwritten; in contrast, as Spivak denotes, Orlando’s patriarchal history is written within the patronymic sign system as ‘father’ (11). Woolf’s system leads to the specter of military, authority, patriarchy and descends into envy, murder, and death. Woolf’s subtext of the violence against women is not an abstract quote inserted into a text but rather that it is the text.

Scene from Djanet Sears, Harlem Duet (adaptation of Othello)

Derrida’s hauntology mobilizes “the specter haunting Europe (the specter of revolution) from the first sentence of [Friedrich Engels’ and Karl] Marx’s The Communist Manifesto together with a famous literary specter, the ghost of old King Hamlet from the opening scene of Shakespeare’s play, to give figuration to the hauntings of history, the traces of the past that persist to question the present. The specter appears to summon the living to undertake a rethinking of the past; it calls, in Fredric Jameson’s words, ‘for a revision of the past, for the setting in place of a new narrative’” (Derrida 43). The new narrative is where Woolf opens her text, a narrative form that belies the patriarchal narrative strategies, by throwing the inkpot, as it were, at the textual system by instead encoding potential interpretations and defying meaning: “Like the deconstructive stress on instability,” explains Derrida, “the specter represents an impossible incorporation: as a revenant (returning) the ghost has no beginning, only repetitions. Present and not present at once and at the same time, it seems to be in a process of ‘becoming-body’, but never quite achieves the materialization toward which it gestures” (Derrida 6). Colin Davis imparts that “Derrida’s specter is a deconstructive figure hovering between life and death, presence and absence, and making established certainties vacillate” (McClallum 11). Woolf takes the established patriarchal certainties and vacillate them in order to disrupt the ancient voices that reside there. Woolf’s ancient voices include the colonial powers staking global territory and expanding empires, as well as representatives from the male dominated canon whom Orlando, as both male and female, meets.

Kristeva and Intertextuality

“Or to offer her his hand for the dance, or catch the spotted handkerchief which she had let drop” (“Orlando” 19) is Woolf’s allusion to Desdemona’s handkerchief, a trope that led to her death on the bed, a symbol, that Woolf offers intertextually to the reader. Julia Kristeva coined the post structuralist theory of intertextuality in 1974; however, intertextuality (intertextualité) is often a misused term. It is not one writer’s, in this case Shakespeare’s, influence of upon Woolf but how the variant elements of the textual systems infuse the work before, during, and after production (Kristeva 15). The “spotted handkerchief,” thereby, is not merely an inserted Shakespearean allusion but it is infused within Woolf’s inner and ancient voices, voices informed through a complex polyphonic system of semiotics, education, and tradition. As part of a system, the handkerchief that Woolf adapts could have permeated while she was in her father’s library. Intertextuality is defined in La Révolution du langage as “the transposition of one or more systems of signs into another, accompanied by a new articulation of the enunciatively and denotative position. Any signifying practice is a field (in the sense of space traversed by lines of force) in which various signifying systems undergo such a transposition” (Kristeva 15). Kristeva’s use of gramme, or that which is written, is used to designate the basic, material element of writing – the marking, the trace (14). The notion of space in which systems undergo transpositioning is apt in Woolf’s work; for example she takes the literary and cultural systems and makes them travel through time to demonstrate powerful association with gender and nation and the subsequent amnesias that are constructed.

The Othello Project, by Rod Carley (1995)

In the same way, Woolf is also interested in the historical marking related to the absence of women’s voices. The cultural marking is represented comparatively in the form of the intertextuality practiced by Woolf in her work. It is here where the trace of the violence against women is found, a transmission rather than an insertion of text. “Violence is all” (21) is coined by Orlando’s narrator explaining the multidirectional influence of literature, nation, and gender: “Thus, if Orlando followed the leading of the climate, of the poets, of the age itself, and plucked his flower in the window-seat even with the snow on the ground and the Queen vigilant in the corridor, we can scarcely bring ourselves to blame him” (21). Woolf’s work, similar to Kristeva’s theory, is a diffusion of literary residue, a process of how language operates with previous usages, the dissonances, and the collisions among them, as well as the engagement with a broader field, extended from or inverted within a specific word or quotation. Who then is to blame? Woolf pursues the question by using the very “classic” texts written to identify the patriarchal influence not only in her work but also in its relationship to violence against women. There are also instances, moreover, when the narrator silences or denies voice to female characters, such as Sasha being untranslatable (34); as well, Sasha’s real name is given by Orlando to a fox he owned as a child, an animal that his father kills (33). Sasha, “who might drop all the handkerchiefs in her wardrobe” (31) is also the figure whom Orlando wishes was Desdemona (43).

Erica L. Johnson explains that “one way of responding to the novel’s pronounced gaps in representation is to piece together what material markers there are [and] that it is prefaced by her [Woolf’s] attention to that which is not apparent through the text” (116). Here, Johnson brings forward of Derrida’s hauntology theory in association with Orlando. Woolf’s meta-literary devices in Orlando make the invisible and silent forms present; or “to be haunted is to hear silence and to perceive that which is invisible” (110). What exactly does this mean and how are the silences perceived in Orlando? I returned to the passage in Woolf’s work that seems to haunt me: Orlando’s (re)memory of Shakespeare’s Othello (5.2.102):

This passage, that “rose in his [Orlando’s] memory?” (17) marks Derrida’s hauntology, as well as Kristeva’s intertextuality. The scene presents Orlando seeing Shakespeare as a ghost-like figure who haunts Orlando much like Hamlet’s ghost haunts his son. Orlando rhetorically asks the specter, “Tell me … everything in the whole world” (17). Woolf’s haunting, through the (re)memory of Shakespeare, brings forward, the presence of violence against women represented in the allusion to Desdemona, the suffocated woman in her bed, who is killed by Othello (an analysis of the relationship between Othello and Desdemona, as well as Iago will be taken up in another entry). Present in its silence is Orlando’s amnesia or the bracketing off of the play’s next line by Emilia, “that I may speak with you” (5.2.106). Woolf makes present the canonical history of Shakespeare and associates it with the violence in the silencing of Emilia’s voice. As Johnson explains, “the dynamic of haunting not only enables those living in the present to become aware of histories that have been erased by the dominant historical narrative, but also potentially signifies the unrepresentational moment of trauma of an individual’s experience of terror or the collective trauma” (110). In making Emilia’s “speaking” absent (“No, I will speak as liberal as the north”) (5.2.226) Woolf indeed makes it “present.” Woolf brings forward the absent voices of women who were present yet undocumented, by keeping them undocumented.

The erasure of Emilia’s voice and her request “to speak” function on two levels: Orlando, informed by his ancient voices, does not recall Emilia’s voice and therefore the silence in history signifies the “moment of trauma.” Woolf, however, shifts this articulation when Orlando is a woman and in that representation “she” remembers, through her ancient voices, Desdemona and Emilia’s trauma, especially when Orlando is asked to be married: “was it impossible then to go for a walk without being half suffocated” (Woolf 94). Orlando, in speaking that she is “half suffocated” shows a shift in the patriarchal patterning, the silence is remembered while Orlando, as a woman, and is present.

Woolf recognizes, not only the violence embedded in text and the absence of the woman’s voice to speak it, but the textual systems that perpetuate the violence of racism that Othello, as Other, is politically, socially and culturally subsumed by, a patriarchal and imperial structure that (re) constructs his representation. The complexity of Woolf’s association, like Kristeva’s theoretical analysis, does not attempt to pin down “meaning” but rather to evoke additional associations and codes that nudge the reader to a certain amount of “accountability” in following the trace lines embedded through tradition, education, and text. Spivak delineates the theory of trace: “To follow this line would take us away from any recognizable task of feminisms in brief compass. As we have noticed, in the discourse on democracy, women are never forgotten, but invoked only as a trace of the many ‘outsides’ of democracy.” (106). Woolf does not attempt to contain the “outside-edness” of women’s space but alternatively reveals its very uncontain-edness, which in itself, as Derrida argues, is revolutionary.